PC and IR

PC, the Program Counter

PC is a 32-bit hidden register.The PC is a poor description for what a PC does. It does not count programs, and is not really a counter at all. The PC holds the address of the current instruction being executed. At times, the PC may hold the address plus 4, attempting to anticipate the "next" instruction to be executed.

Recall that, in MIPS, instructions are 4 bytes long and thus use up 4 consecutive memory locations. Since instructions are words, they must be stored at word-aligned addresses, i.e., at addresses divisible by 4.

If you inspect the low two bits of the PC (i.e., PC1..0), you'd notice that they always end in 00.

Unless a branch or jump occurs, PC is updated to PC + 4, the address of the next instruction in memory. Notice that the next instruction in memory is not the same as the next instruction to be executed. It's possible for the next instruction to be executed to be some other instruction besides PC + 4.

IR, the Instruction Register

IR is a 32-bit hidden register.At least, IR has a reasonable name. This register actually stores an instruction. In particular, it stores the instruction given by PC.

By storing an instruction in a register, we can use the output of the register to control other parts of the CPU, so the instruction can be executed.

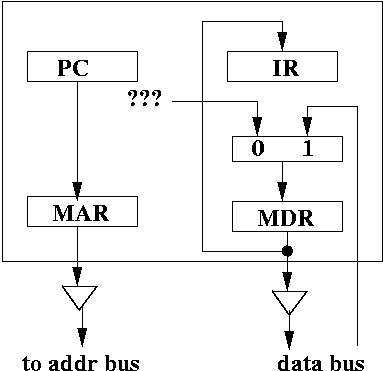

How PC and IR are used in conjunction with MAR and MDR

Where is this new instruction? It's in memory. We need to get that instruction out of memory, and bring it to the CPU where the CPU can execute it.

To get the new PC to memory, we need to get its address to the address bus. However, the only register we have that can access the address bus is the MAR.

So, we need the datapath of the CPU to connect the output of the PC to the input of the MAR. That's not too hard. We simply attach a bus from the output of the PC to the input of the MAR, and we're done.

What about the IR? The IR contains a new instruction. That instruction is going to be provided by memory, and placed onto the data bus. The CPU then reads the instruction off the data bus and places it in the MDR.

We need one of the outputs of the MDR to go the inputs of the IR. The other output is going to be used to store data into one of the user-visible registers. However, we'll deal with that later.

A Modified Diagram

So PC feeds directly to MAR. We'll need to add a MUX later on to the diagram, because the MAR can get its address from either the PC (when it needs to fetch an instruction from memory) or from some other location to be specified later (when it needs to fetch data from memory).

The output of MDR goes to IR. The input to MDR can either come from some place in the CPU (we just label it ???) to indicate this is data being sent to the data bus, or it can come from the data bus itself (when we're doing a load operation).

One way to understand this diagram is to draw it out yourself, and see what you think as you draw it. Sometimes, staring at a complicated diagram doesn't give you as much insight as drawing it.

Also think about where the information has to flow when you are doing the following operations:

- Placing an instruction address from PC to MAR.

- Placing an data address to MAR from someplace to be specified later (the diagram above doesn't allow you to do that--what needs to be changed?)

- Loading data into the MDR from someplace to be specified later

- Loading data into the MDR from the data bus

- Sending the output of the MDR to the IR

- Sending the output of the MDR to someplace to be specified later (the diagram above doesn't allow you to do that--what needs to be changed?)

Summary

Both of these registers are 32-bits and both are "hidden". That is, they are not directly accessible by the assembly language programmer.

PC is not a particularly good name. It fails to describe its purpose clearly, and can be confused for phrases "personal computer" and "political correctness". Nevertheless, for historical reasons, we use the term PC to refer to the address of the instruction.

PC and IR must interact with MAR and MDR because MAR and MDR are the registers that lie between the CPU and the data and address bus. Later on, we may decide to remove the MAR and/or the MAR for efficiency reasons.