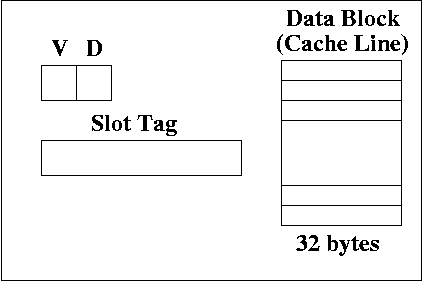

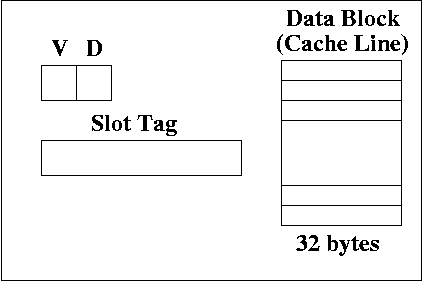

Each slot contains a valid bit, a dirty bit, a slot tag. The slot tag contains some number of bits, which depend on the cache scheme. There is also a data block (also called a cache line). This data is a copy of the the data in the memory.

In our example, the data block has 32 bytes. Think of this as a byte array indexed 00000 up to 11111. Each byte of the data block is a copy of a byte in RAM.

Any of these three methods generates an address, and causes data to be moved from memory to a register or from a register to memory. (Fetching an instruction places the instruction from memory to the instruction register).

Let's pick one of the three ways of generating an address: loading a word.

Suppose you have the following MIPS instruction:

lw $r4, 0($r3)

The address generated comes from R[3]

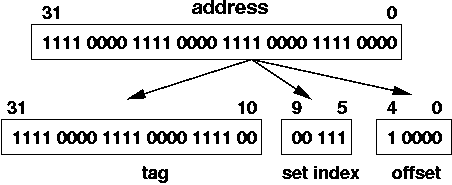

Suppose the address stored in $r3 is:

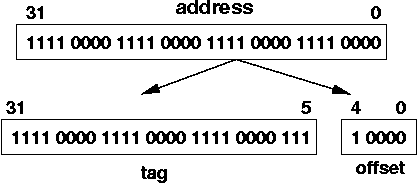

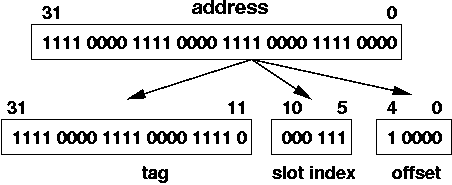

0000 1111 0000 1111 0000 1111 0000 1111

We're going to see how to use this address to find the data

stored at that address in cache.

We're going to refer to an address tag and a slot tag. The address tag comes from an address generated by load/store, or the fetching of an instruction from the PC. The slot tag is located in the cache hardware, in each slot (not surprising!).

The slot index uses up 6 bits because there are 64 slots, and you need 6 bits to label each slot with a unique UB number (recall the formula ceil( lg ( 64 ) ) = 6).

That leaves 21 bits for the tag. Thus, each slot in a direct mapped cache with the cache specs given earlier has 21 bits for the tag.

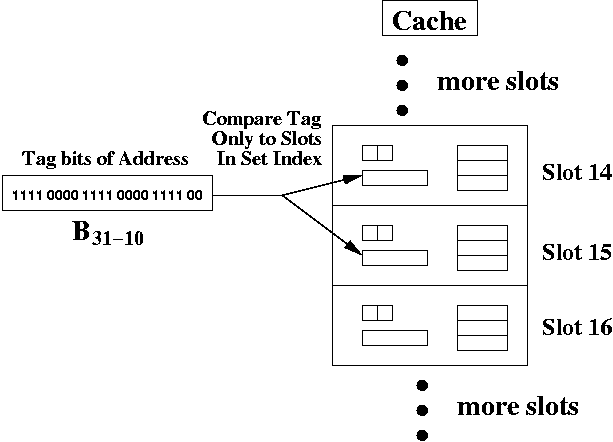

In this case, since we have 32 sets, we need 5 bits to specify the set. Thus, instead of a slot index, we have a set index.

The address we've been using in our example specifies set 000 11

There should be, at most, one slot whose tag matches the address tag, and whose valid bit V = 1. If there is a match, this is called a cache hit. If there is no match (i.e., the tag of the address does not match any of the tags in the slots, of if they do, the valid bit is 0), then there is a cache miss.

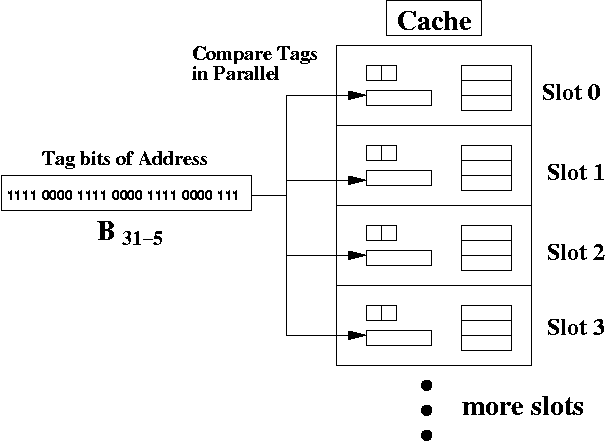

The diagram below shows the comparison. Only 4 slots are shown to save space. The cache hardware compares the 27 bit tag from the address to the 27 bits tags in all 64 slots, in parallel.

If there's a hit, then the offset from the address is used to access the bytes in the data block (e.g., cache line). In this case, the offset is 1 0000 which is 16ten. So, if there was a cache hit, you would look at element 16ten of the data block array. The array is indexed starting at 0.

A cache hit is defined as follows:

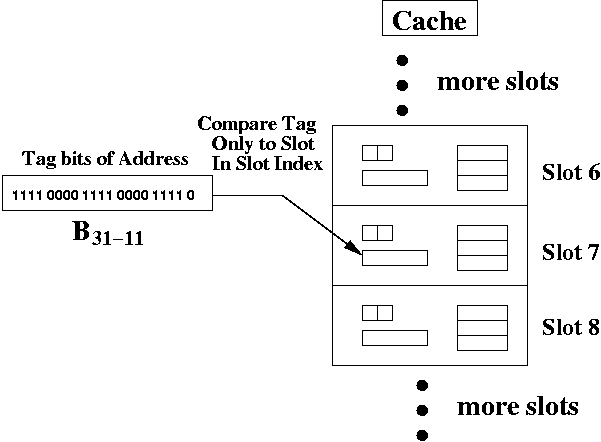

The hardware is simpler for a direct mapped cache than a fully associative cache, because you only have to compare the address tag to one slot. The cache hardware only picks the slot is determined by the slot index address bits. In this case, those are bits B10-5.

However, direct mapped cache do not fully utilize the cache slots. There may be collisions to the same location in memory.

The hardware is simpler for a set associative cache than a fully associative cache, because you only have to compare the address tag to two slots. The cache hardware only picks the slot is determined by the set index address bits. In this case, those are bits B9-5.

Set associative caches are a reasonable compromise between fully associative caches (whose hardware is complex enough to actually slow down the access of the cache) and a direct mapped cache (which may suffer from problems of collisions to the same slot index).

We can index the data block from 00000 up to 11111 (as 5-bit UB numbers).

How can we find the address of the byte in a particular slot. For example, we may be in slot S, looking at byte B.

Here's how to compute the address from the data block to RAM address.

It's critical that we use powers of 2 for number of slots, number of sets per slot, and number of bytes in a data block. That way, we can pick out bits from the address. If we didn't use powers of 2, then it would be more challenging to determine anything (think about why this is).

If the dirty bit is set, then we must copy the data block back to RAM (assuming a write-back policy). If not, then no copying is done.

Then the new data block is copied, the tag bits are updated, the valid bit set to 1, the dirty bit set to 0, and the desired bytes sent back to the CPU which requested the bytes to begin with.

Clearly, a cache miss can be slow to handle, and we hope that a program has sufficient temporal and spatial locality that cache misses are infrequent compared to cache hits.

An address is divided into tag bits, offset, and possibly slot or set index, depending on the caching scheme. The address tags bits are compared to slot tag bits. The slots picked for comparison vary according to the caching scheme.

For a fully associative cache, the address tag bits are compared to all slot tag bits, in parallel. This generally creates hardware so complex, that it slows down the speed of the cache.

For a direct mapped cache, the slot index bits from the address are used to pick exactly one slot. The address tag bits are compared to the slot tag bits for that one slot. If it matches (and it's valid), there's a cache hit.

For a set associative cache, the set index bits pick exactly one set. Each set has 2k slots (where k > 1). The tag bits of the address are compared to each of the slots in the set, in parallel. In our example, we had two slots per set, so only the tag bits of two slots were compared to the tag bits of the address.

Only slots has valid and dirty bits. The address do not have such bits.