A Simple Model of Memory

Introduction

A basic computer consists of a CPU, which processes instructions,

memory, which stores data and instructions, and a bus, that connects

the CPU to memory.

We're going to focus on memory in these notes. Initially, we'll

have a very simple model of memory, then we'll make it a little more

realistic.

Memory as a Large Array

It's useful to think of memory as a large array. Since you've

been programming for several semesters now, arrays are something you

should be experts with.

Think of memory as a large one-dimensional array.

But arrays have types! So what type of array should memory have?

Each element of memory contains a byte. Let's now define

two terms

Definition An address is another name for the index of

an array. It's often called address rather than index, when used

with memory.

Definition Byte-addressable memory means that at each

address, there is a byte. That is, memory consists of an array

of bytes.

We could have nybble-addressable memory (each address stores

a nybble) or bit-addressable memory (each address stores a bit)

or word-addressable memory (each address stores a word).

However, the most common use of memory is to have one byte at each

address.

Multiple-byte quantities

How do you store multiple byte quantities in memory? For example,

suppose you want to store 32 bits. One way to store this is to break

the 32 bits up into 4 bytes, then store the 4 byte quantity in

consecutive order. For example, if the first byte is stored at 1000,

then the next 3 bytes are stored at 1001, 1002, and 1003.

Endianness

As it turns out, storing multiple bytes is a little more complicated

than that. For example, when you break a quantity into 4 bytes, and

store it in memory, there's two popular ways to do this. One way

stores the least significant byte of a four byte quantity in the

smallest address first (at address 1000, in this example), and works

its way to the most significant byte (at address 1003). This is

called little-endian ordering.

If you store the most signficant byte first (at address 1000),

and work your way to the least significant byte (at address 1003),

that's big-endian ordering.

To make things more complicated, this ordering is only performed

on quantities that the CPU handles. If you're storing a structure,

for example, a structure can be broken down into bytes, halfwords,

and words. The entire structure usually does not have

an endianness, but its individual components do. For example, if

a structure contains an array of int, then each element has

an endianness, but if you look at the array's elements, they always

increase in addresses. Thus, & arr[ i ] is less than

& arr[ i + 1 ].

Word-alignment

To make things even more complicated, word quantities are

often word-aligned (first byte stored at an address divisible by

4), while half-words are half-word aligned (first byte stored

at an address divisible by 2), and double-words are double-word

aligned (first byte stored at an address divisible by 8).

How does a computer know about words? It turns out that there are

instructions to read and write from memory, and those instructions

often specify a size. For example, if the instruction is to load

a word, then the word must be at a word-aligned address. If it

loads a byte, then it can be at any address. We'll explain

what it means to load a word momentarily.

"Dumb" Memory

As it goes, it's the CPU that is aware of endianness and aware

of word alignment. Memory is "dumb". It merely access the bytes

it's being asked to retrieve or to write to. It does not place

meaning to the bytes, like the CPU does.

Basic Memory Operations

The CPU performs two kinds of operations on memory. It can

either read from memory (this is called a load), or it

can write to memory (this is called a store).

Read

When reading from memory, the CPU

- specifies an address in memory,

- plus the number of consecutive bytes it wants (usually

1, 2, 4, 8 bytes are the only possibilities), starting at the

address specified,

- plus the fact that it wants to read from memory

How does it do this? The address is sent to memory via the

address bus. The number of bytes can be sent in a signal through

the control bus. Also, the fact that the computer wants to do

a "read" operation can be sent through the control bus.

Once memory has received the signals, it retrieves the data from

memory, and outputs the data to the data bus, and alerts the CPU that

the quantity is now available, at which point the CPU will then read

the data off the data bus, and store the information internally in a

register.

Write

For a write operation, the CPU

- specifies an address in memory,

- plus the number of consecutive bytes it wants to store (usually

1, 2, 4, 8 bytes are the only possibilities), starting at the address

specified,

- plus the fact that it wants to write from memory

- plus the data it wants to write to memory

How does it do this? The address is sent to memory via the

address bus. The number of bytes can be sent in a signal through

the control bus. The CPU also informs memory it wants to do

a "write" operation through the control bus. Finally,

it places the data from the CPU onto the data bus (usually from

a register).

Once memory has received the signals, it reads the data off the

data bus, and then stores the data at the address specified.

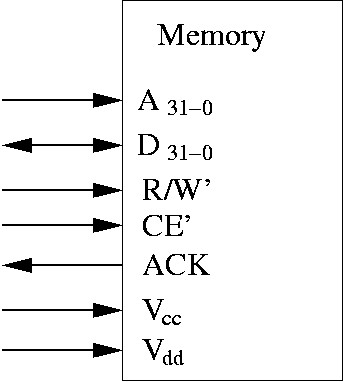

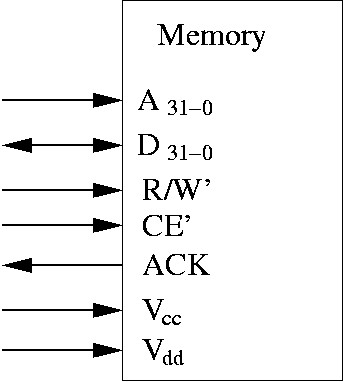

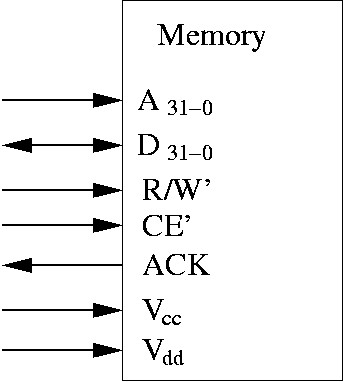

Pin Specifications

Once we know the operations, we can begin to specify what "pins"

the memory contains. Pins refer to inputs or outputs of the memory.

If you've ever seen any hardware (say, a CPU or memory), you will

sometimes see pins. CPUs especially have lots of pins. Some of

those are inputs, some are outputs, some are both input and output.

These are the various pins memory should have, assuming 32 bit

addresses and word sizes of 32 bits.

- A31-0 32 pins for the address bus.

- D31-0 32 pins for the data bus.

- R/W' A one bit quantity that indicates whether a read or

write operation is requested of memory. When R/W' = 1, a

read is requested by the CPU to memory. When R/W' = 0, a

write is requested by the CPU to memory.

- CE' A one bit quantity called chip enable.

If CE' = 0, then the CPU wishes to do either a read or

write operation on memory. The exact operation is specified

by R/W'. If CE' = 1, then the CPU does not

want to do either a read, nor a write operation. After all,

the CPU may not always want to perform an operation on memory.

We write CE' (CE with a prime after it) to indicate that

this is an active-low signal. An active-low signal

means that the signal is "active" when the value is 0. Thus,

chip-enable is enabled when the signal is 0. If it were active-high,

we would leave the prime off (write it simple as CE), and

then 1 would make CE active, instead of 0.

- ACK This is a 1-bit output pin that stands for

"acknowledgement", that informs the CPU that either the read or

write operation has been successful. When the value of

ACK goes to 1, the CPU knows the memory has completed the

operation. The CPU responds by setting CE' to inactive

(i.e., it sets the value to 1).

- Vcc, Vdd. These pins are

for power, and have nothing to do with data, address, or control.

The chips require power to run, and these provide the voltages

and currents to make it run.

Diagram of Memory

Some comments:

Some comments:

- The address pins are input only (i.e., A31-0).

There are 32 pins. This is connected to the address bus.

- The data pins are bidirectional (i.e., D31-0).

They can be used to place data into memory or copy data out of memory.

There are 32 pins. This is connected to the data bus.

- One input pin for R/W'. This is connected to the control bus.

- One input pin for CE'. This is connected to the control bus.

- One output pin for ACK. This is connected to the control bus.

- One input pin for Vcc and Vdd.

This is hooked to power and ground.

Why it's Simplified

We've left a few details out. First, we said there's a way to

specify the number of bytes to be retrieved. The memory chip shown

above does not have such pins. They could be easily added. For now,

you can assume that it retrieves 32 bits at a time.

In reality, it's probably easier to fetch 8 bytes or more, and then

pick out the bytes you actually need. The data bus actually controls

how much data you can get at a time.

Also, we assume this chip contains 232 bytes (which

is 4 Gigs). In reality, you usually have far less memory than this.

Usually, you only have maybe 1 G of physical memory. In the past,

even 64 M of memory was quite a lot.

Also, the memory system is often built from many smaller memory

chips, and logic that connects them all. Furthermore, if you do

memory-mapped I/O, not all addresses are devoted to real memory.

Some are devoted to I/O devices.

These details are lead to additional complication, even if it's

more realistic.

Web Accessibility