Combinational logic circuits are implementation of Boolean functions. They compute their outputs as functions of their input. They do not have any memory elements.

Sequential logic circuits, implement functions with state. That is, they keep information internally (think of this information being stored in data members of an object). The output of a sequential circuit depends not only on the input bits, but also on the internal state.

It turns out, for sequential circuits, it's easier to design with a clock.

So, what's a clock?

Most people think of a clock as a way to tell time. Why would a computer need to know how to tell time?

A clock, on a computer, isn't the same kind of clock used in your home, or on a watch. If you've ever bought a computer, one of the more important features it the clock rate. For example, you may buy a machine that's running at 2 GHz. Do you know what 2 GHz refers to? It refers to a clock!

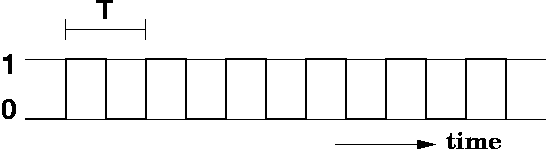

Here's an example

A clock is a device that alternates between 0 and 1, repeatedly. We can define key features of this plot.

The most important is the amount of time it takes before the signal repeats. This time is called the period, which we call T. In this period, there is a single cycle.

The period is related to the frequency, f. In fact, they are inversely related f = 1/T. The frequency means how many times the waveform repeats per second. The unit of measurement for frequency is Hz (pronounced Hertz), and is the same as s-1 (inverse seconds).

The higher the frequency, the shorter the period of one cycle. When you hear a clock is 1 GHz, this means there is 109 cycles per second (G = giga = 109).

Consequently, the period is 10-9seconds, which is a nanosecond.

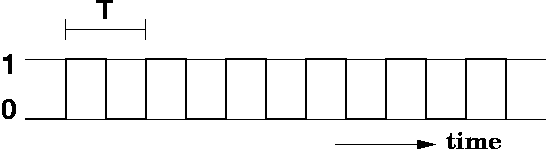

Look at one cycle of the clock.

In this one cycle, the clock has an output of 1 for part of the time, and 0 for part of the time. Now it appears that it is 1 for half the time (i.e., for T/2), and 0 for half the time, but it turns out it's not that important for the clock to have that property. It's OK if the clock is 1 for 3/4 T and 0 for 1/4 T, even though it's fairly common for it to be T/2 and T/2.

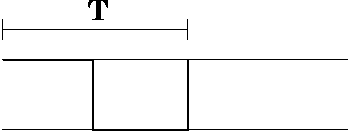

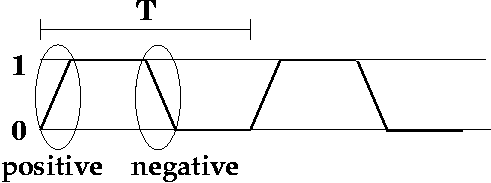

The clock looks more like:

On the diagram, you see the label "positive". This indicates a 0 to 1 transition. That transition is considered a positive edge (since it has a positive slope). The 1 to 0 transition is called a negative edge (since it has a negative slope).

A flip flop can store 1 bit of information. In a positive edge-triggered flip flop, the value stored in the flip flop can only change when a positive edge occurs. Thus, it can only change at the circled portion (shown in the previous figure) that says "positive".

At all other times (i.e., when the clock is steady at 1, or steady at 0, or transitioning from 1 to 0 on a negative edge), the flip flop holds its value. That is, its value can not change.

Thus, edge triggered flip flops can only change its values at the edge of a clock.

You might wonder why flip flops are designed this way, when combinational logic circuits (i.e., AND gates, OR gates, etc) do not use any clocks.

It turns out that its easier to design digital circuits which can only change values at an edge. This will be explained later.

If you run a CPU with a clock rate that's way too high, then it may not complete certain computations before the clock edge appears.

It's similar to a conductor conducting an orchestra. He can only conduct the pace so quickly before the players can not keep up with pace without making mistakes.

In a computer, it takes time to perform computations. As technology gets better, this time can be shortened, and the clock can therefore be made quicker.