The second approach is to teach circuits to you top-down. The advantage of this approach is that it emphasizes abstraction, and then fill in the details later on. It tries to give you the big picture first, and only once you have that, does it go into details.

So far, personal experience seems to show that the bottom-up approach works better. Students grasp the concepts more easily. Perhaps that's because most humans reason that way. You see many simple examples, then you learn to generalize, and talk about the simple examples through a general theory.

Still, there's an appeal to introducing circuits top-down. You describe behavior first, in an abstract, mathematical way. You reveal the actual details of implementation later on. You talk in terms of inputs and outputs, but not what's in the box.

For some students, it's important to see what's in the box. Knowing how things really work seems to aid some people's understanding. However, once you explain what's in the box (say, logic gates), you discover that even those details are abstractions.

You're still not presenting the "complete" picture. For example, once you learn that a black box is implemented by logic gates, you still haven't learned that logic gates are implemented using transistors, or the details of the physics behind transistors, or the manufacturing process, etc.

Revealing more and more about how something works may, ironically, make it harder to understand. For example, it's not easy to learn semiconductor physics. On the other hand, that's mostly a detail of implementation. It's hard to argue that knowing the semiconductor physics actually helps you understand how circuits behave. They may help you understand implementation, but that's a different concept.

At some point, you just have to believe the abstraction explains it as well as you need to understand it, and not worry about how the details are implemented.

If that seems like a cop-out, it probably is, but people do this all the time. How many people are more than content that all their electronics work, and they know how to operate them, without knowing all the details? You could spend forever trying to master everything related to a computer!

What most people mean by black boxes is that it has inputs and it has outputs, and it does something to the inputs to generate the outputs, but that you don't particularly care how the outputs are generated.

It's actually very similar to describing an object or a function. Someone tells you how, say, printf() behaves. However, they don't tell you how it's implemented. Effectively, this function is a black box. And think---do you care how printf() is implemented? Do you even know how printf() is implemented?

That's the great thing about black boxes. You just need to describe its behavior. Effectively, this behavior is the interface, with the implementation hidden away "underneath" the box.

A "black box" is basically a function. Functions have inputs and they have outputs. More precisely, a mathematical function maps elements from one set (which are the inputs) to elements of a second set (which are the outputs). The first set is called the domain, the second set is called a co-domain.

A function may have more than one input. One way to describe

is using tuples. The following is a Cartesian cross product.

S1 X S2 X ... X SN

A tuple is basically a structure, with N values. Thus,

(s1, s2, ... , sN) is a tuple.

Notice that I use lowercase "s" within the tuple. That's because

si is an element of Si. That is,

tuples consist of N positions. Each position has an element

drawn from set Si.

If you're confused, we can clarify with an example. Here's

a specific tuple.

bool X int

This represents a set. This is the set of all

possible boolean, int pairs. For example, (2, true),

(10, false), (-3, true) are all in this set.

However, (2, true, 4) is not in the set (too many elements),

and (true, 2) is also not in the set (types don't match).

Tuples allow us to describe functions of many different arguments and multiple return values.

Fortunately, we don't need to use the full generality of tuples.

We're going to concetrate on Boolean functions. These functions have tuples as inputs and tuples as outputs. But they're restricted in the following way.

That is, the inputs can only be set to 0 and 1.

That is, the outputs can only be set to 0 and 1.

What does it mean to say that the outputs are only dependent on inputs? This means that if the black box has, say, 3 inputs and 1 output, then if the input were, say, (0, 1, 0), and the output was 1, then the output will always be 1, given that input.

Functions compute outputs on inputs only. You provide a specific input, and it always produces the same answer for that specific input. It may produce a different answer for different inputs, but it's consistent on the answer it produces.

To give an analogy, the solutions to a multiple choice exam are a function. They map integers (the question number) to letters (the answer). If you see the answer to number 3 is D, then it should ALWAYS be D. You don't expect the answer to be D one day, and, say, C the next. (Let's imagine the test is mathematics, and no one has made a mistake on the solutions).

If the answer were D one day, and C the next, the the mapping would not be based purely on the question number. Some other non-input would be affecting the answer.

By that, I mean that it takes some time to compute an output. It's not a lot of time, but it's not zero either.

The last part is something we need for a realistic circuit. A circuit implements Boolean functions, but still doesn't convey some of the real aspects of a functioning circuit.

Functions, in general, only describe a mapping. They don't describe how the computation is done, nor do they describe how long it takes that computation.

However, circuits are physical structures, and as such, they take time to compute outputs, so we mention this fact about black boxes.

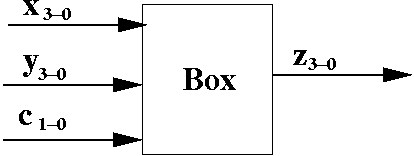

Usually, we'll follow the convention that data inputs start with the letter 'x' (plus a subscript) and control inputs start with the letter 'c'.

However, sometimes it will be convenient to label the data inputs into two sets. In that case, we'll refer to 'x' and 'y' as data inputs.

We'll demonstrate how all this works with an example in a moment.

We can think of this black box as an ALU, with the following functionality.

| c1 c0 | Operation |

| 00 | Bitwise AND (X & Y) |

| 01 | Bitwise OR (X | Y) |

| 10 | Flip Bits for X (~X) |

| 11 | Add X + Y (X + Y) |

Thus, c1 c0 control what the ALU does with the data inputs. If c1 c0 = 00 then a bitwise AND operation is performed on the individual bits of X and Y.

Thus, zi = xi & yi for 0 <= i <= 3

However, there are machines that are more accurately described when they have internal state. Think of a soda machine that dispenses soda for 75 cents. Imagine that it dispenses only one kind of soda, and once you place in 75 cents, it automatically gives you the soda.

You go to the machine and place in 25 cents (that's your input to the machine). Nothing comes out. Then, you enter in 25 cents. Again, nothing comes out. Finally, you place in 25 cents, and a soda comes out.

This soda machine is not "functional". That is, it does not behave like a mathematical function. In a mathematical function, given the same input, you should always get the same output.

However, twice, when you entered in 25 cents, the output was nothing, but the third time, you got a soda as output. A function always produces the same results given the same input.

So what's going on? Obviously what's going on is the machine stores some information. This information is called state.

State is not something so unusual. If you've done object oriented programming, you already understand the idea of state. For example, suppose you have a stack object. You want to know the number of items in the stack. So you call a size() method. That size() method takes no arguments.

Yet, the value returned by size() (i.e., its output) depends on some internal information. In particular, it depends on how many elements are on the stack, stored within the object.

If size() behave like a regular mathematical function, then whatever output it produced the first time would be the same output it always produced. That's because size() takes no argument, and thus it would be a constant function.

However, size() is not a regular mathematical function. Its output depends not only on the control and data inputs, but some internal information.

We'll label state using q, plus subscripts.

Thus, the output is a function once you consider state. That is, the output is a function of inputs and state.

The answer is similar to how state changes for objects. If you have a stack, you perform an operation (such as pushing an item on a stack) that modifies the internal state.

Thus, the inputs not only affect the outputs generated, but also affect the state. You can think of state as being another kind of output (except its values are not exposed outside of the box) in that you compute the state based on the inputs and (surprise!) on the state itself.

To see what I mean, suppose you had another object who's job is to keep track of a sum. As you add a value to the object, the change in the sum depends not only on the input, but the sum itself.

For example, you're likely to have code that looks like:

void Foo::addValue( int value ) {

sum = sum + value ;

}

sum is basically a state variable. It's being updated

based on itself (a state variable) and an input (called value).

So, both the state and the output are computed from the input and from the state.

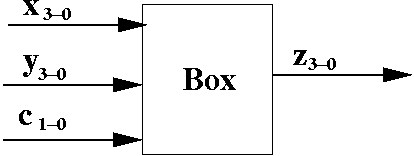

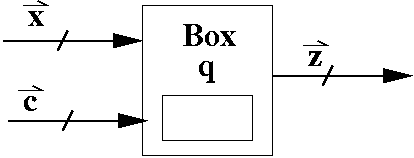

Here's a diagram of how a black box with state looks.

where x are the data inputs and c are the control inputs.

Notice that there is a slash where the wire is drawn. This is to indicate that there may be one or more bits associated with x and c. It's also possible that there are no control bits. This occurs when the box computes a single function. Obviously, when there's only one function, you don't need control bits to select which function to pick from.

The output is labelled z and can also have more than one bit.

Notice that each letter has an "arrow" over it. I'm borrowing notation from the math folks. This arrow means the variable is a vector. Just think of that as a bitvector or a bitstring. That is, the variable stands for one or more bits. To select an individual bit, you just subscript the variable (without the arrow on top).

Think about a stateless black box. To compute the output, you apply a function to the inputs. The output is computed as soon as it is ready. If the inputs change, then the output is recomputed and "output" as soon as its ready.

In principle, this process of computing outputs from inputs can be done continuously. That is, the output changes as fast as the input change. In reality, this has limitations.

To illustrate, imagine the following scenario. You have an assistant, who will record the letter grade of a particular exam. The letter grades are assigned as follows: 93-100 is an A, 86-92 is a B, 74-85 is a C, 65-73 is a D, and 64 and below is an F. The assistant types the grade into a spreadsheet as you read out the names and the scores.

If you read the scores very slowly, the assistant doesn't have to memorize the score ranges and their corresponding letter grades. The assistant can look it the chart, figure out the grade, and record it.

Suppose you start to read the score faster and faster. It will become harder and harder for your assistant to keep up. Eventually, the assistant will start skipping scores, or misenter them, because s/he can't process the grades as fast as you speak them.

This phenomenon can happen to a stateless black box circuit. If the inputs change too quickly, the outputs may not reflect each change of inputs. You want to change inputs slower than the speed at which the box can compute the values (although, that isn't strictly necessary---nevertheless, there is an upper-bound at which you can change the input and expect the output to match that rate).

With state, things get more complicated and confusing. State is computed not only from the inputs, but also from itself.

Think about the class that updates a sum. The sum is computed from an input value and itself. Imagine if this were being computed as fast as possible over and over again. You might repeatedly add to a sum far more times than you want. Although it's hard to imagine this in a program, it could happen in a circuit.

Why do programs behave better?

The answer? Programs process each step discretely. That is, it performs one step of a program, then the next, then the next, and so forth. This is one reason you can step through programs using a debugger.

Circuits fall in two categories. Those that process inputs continuously, and those that process inputs at discretely. The entire field of analog electronics is about processing inputs on a continuous basis. However, making analog electronic circuits often requires a knowledge of differential equations. You can design logic circuits (which process inputs discretely) without a knowledge of differential equations.

What do I mean by processing the inputs discretely? In order to explain this, I need to explain what a clock is.

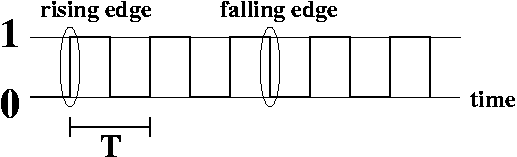

Here's a diagram of a clock output.

This is a graph that plots time across the horizontal axis, and a discrete value of 0 or 1 across the vertical. Basically, a clock is a signal that changes from 0 to 1 over and over, at regular intervals.

Here are some key terms you should know about a clock output.

Strictly speaking, this doesn't have to happen. As long as the period between rising edges is T, and the period between falling edges is T, then the clock is still useful.

We're going to synchronize the black box with state to a clock. The output and the state can only change once per period. We arbitrarily say that the output and state can only change during the rising edge of a clock. During the other times when there is no rising edge, the output and the state will hold its values.

Thus, at every rising edge, the output is computed as a function of the input and current state. Also, at every rising edge, the new state is computed from the inputs and the current state. Again, it may be useful to think of this like an assignment statment

sum = sum + input ;

where the new value of sum is computed from the old value of sum plus the input.

The second kind of black box is a black box with state, where you can think of state like the values stored in the private variables of an object. For such black boxes, we introduce the notion of an internal state and a clock.

The clock forces the circuit to update only at very specific points in time. In particular, the circuit only updates the state and the outputs at rising edges.

Both the output and the new state are computed as functions

of current state and the inputs.

Z = f( X, C, Q ) // Z is a function of data/control inputs and state

Q = g( X, C, Q ) // Q is a function of data/control inputs and state