One way to implement a truth table is to derive a sum-of-products expression. This is how it's done:

The advantage of this method is that it's easy, and doesn't require much thinking. The disadvantage occurs when you have a lot of minterms. You may draw many gates.

There's a quick and dirty way to implement a truth table.

| Row | x | y | cin | cout | s |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Let's implement one of the two outputs. Let's implement cout.

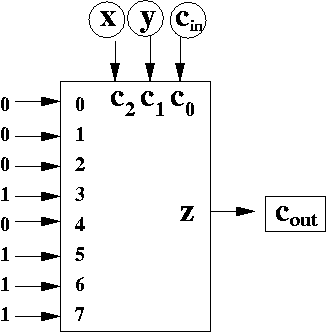

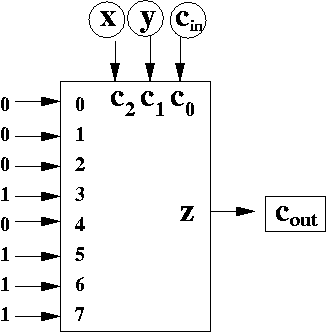

To do so, we use an 8-1 MUX.

How did we create this circuit? Look at the truth table above. Look at the column with cout. That column has the values 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1. That's also exactly the hardwired inputs being fed into the MUX, in exactly the same order.

Look at the control inputs. They are fed in with x, y, and cin. Again, that's exactly the same order the input variables appear in the truth table.

Let's see what's happening. Consider row 5. We select row 5 when the input variables xycin = 101. Recall that 101 is 5 in UB.

Thus, when c2c1c0 = 101, that is, when the control bits of the MUX are set to 101 (which is 5 in UB), then input x5 is selected. In the example, above, input 5 is set to 1, which also happens to be the output of cout when xycin = 101.

In a nutshell, the MUX trick is the following:

However, it would require a 16-1 MUX using the MUX trick.

The reason for using the MUX trick is twofold. First, on an exam, it may allow you to answer an implementation question far quicker than using sum-of-products. At times, you use tricks to answer questions quickly, even if it's not the most "efficient" answer.

The second reason is to make you aware that MUXes can be used to implement truth tables easily, if somewhat inefficently.