Can we do better? Can we make addition faster? Clearly, the answer is yes, otherwise, we wouldn't have this discussion.

| Row | x | y | cin | cout | s |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

We can write the carry-out of this adder using sum of products. However, there is an alternate way of writing the carry out.

Before we discuss how to write it, let's define a few terms first. Recall that we are adding two n-bit numbers: xn-1...x0 to yn-1...y0 which results in zn-1...z0. In a ripple carry adder, we assign a full adder (call it adder i) to add xi to yi. We'll use the ripple carry adders which only uses full adders.

Adder i also has a carry in. We'll call that ci. It generates a carry out, which we'll call ci + 1. When we add the least significant bits c0 = 0. However, we'll simply leave it as c0.

We can write the Boolean expression for the carry-out

in an alternate way:

ci+1 = xiyi + xici + yici

This Boolean expression has the same truth table as above. It even

makes intuitive sense. There's a carry out when any two of the three

bits (i.e., xi, yi, or

ci) have a value of 1. Thus,

xiyi is 1 only when both

xi and yi are 1. And since this

is inclusive OR, all three bits could be 1.

We use the distributive property to rewrite the carry out as:

ci+1 = xiyi + ci(xi + yi)

Let's define two terms:

gi = xiyi

pi = xi + yi

Then, we can rewrite ci + 1 using these two terms, as:

ci+1 = gi + pici

gi is called the generate term. This

always generates a carry out. gi =

xiyi, which is 1 only when

xi and yi are both 1.

Clearly, if two bits are 1, there's a carry.

pi is called the propagate term. pi = xi + yi. This could create a carry, but it may not. We know that at least one of xi or yi must be 1 if pi = 1.

This is called propagate for the following reason. If exactly one of xi or yi is 1, then the carry-in determines whether there is a carry-out of 1 or not. Thus, if ci is 1, there is a carry-in of 1, which will cause a carry-out of 1. If ci is 0, then the carry-out is 0.

To propagate, in this case, means to assist. For example, suppose you are standing in a line. Some one says to hand something forward, say, a piece of paper. Even though you did not bring the piece of paper, you can help move it along (i.e., help propagate it) by passing it to the next person. Similarly, propagating a carry means to move the carry from the previous adder to the next adder.

Mostly, we only care about propagating a 1. We're not that concerned about propagating 0's. That's why we AND pi to ci. By itself, pi may not cause a carry. However, it can propagate a carry-in of 1, by causing a carry-out of 1, if pi is 1.

This is how we do it. First, let's write the c1

which is the carry out for the adding bit 0 of x and y.

c1 = g0 + p0c0

Now, we write it for c2.

c2 = g1 + p1c1

At this point, we've used c1, which we'd rather avoid,

because it means waiting for that carry to be computed. However,

we just defined c1 (see the previous

formula) as g0 + c0p0.

Let's plug that in:

c2 = g1 + p1(g0 + p0c0)

= g1 + p1g0 + p1p0c0

Notice that we no longer have c1. That means

we no longer have to wait for the carry!

Let's go one more step further:

c3 = g2 + p2c2

Again, we would prefer to avoid using c2 since this

requires us to wait for the result to propagate across two adders.

However, we already have a Boolean expression for

c2 (we just computed it a moment ago) that doesn't

use any carries except c0 which we have right

away.

c3 = g2 + p2c2

= g2 + p2(g1 + p1g0 + p1p0c0)

= g2 + p2g1 + p2p1g0 + p2p1p0c0

Already, you should be able to detect a pattern. By following the

same pattern, you'd expect:

c4 = g3 + p3g2 + p3p2g1 + p3p2p1g0 + p3p2p1p0c0

You might wonder, why? Why are we computing carries, if the idea is to avoid using carries?

The idea is to construct a circuit for ci that can be fed into the input of adder i. The carry-out of the adder is not used. In fact, each of the full-adders aren't directly connect to each other. We simply design the circuit for ci and feed it in.

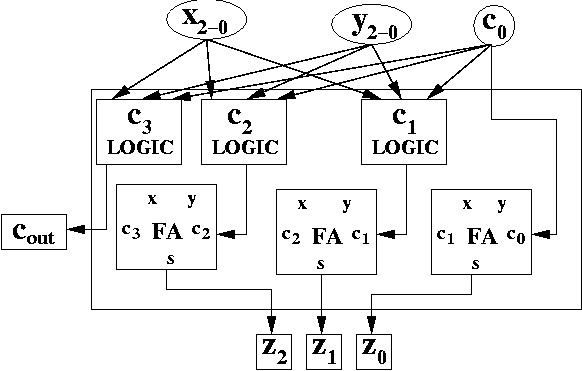

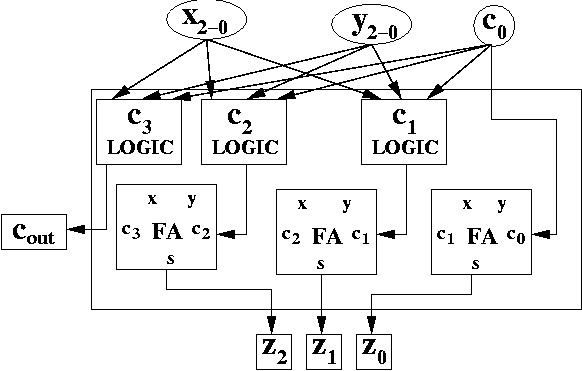

The following is an approximate circuit.

The diagram is incomplete. It's missing the wires from xi and yi to the appropriate adders. As an exercise, redraw the diagram, and add those wires in. Also, draw x2-0 as 3 separate inputs, instead of the one circle drawn in the diagram above. Do the same for y2-0. If you want, you can even draw in the logic inside the boxes that say things like "c3 LOGIC".

What should you understand from this diagram? The key point to observe is the carry out of the full adder is not attached to the carry in of the next adder. Instead, there is logic (as defined by the Boolean expressions from the previous section) that has inputs from xi's, yi's and c0.

Still, it's not quite O(1). Why not? Look at the formula, for say, c4.

c4 = g3 + p3g2 + p3p2g1 + p3p2p1g0 + p3p2p1p0c0

Given ci, there are i terms to be ORed. The largest product term, (in the example above, it's p3p2p1p0c0) has i+1 literals.

If you build everything out of 2-input AND gates or 2-input OR gates, then the best you can do is about O(lg N) where N is the number of bits in the addition. Still, that's far more efficient than O(N).

This is one lesson in hardware. Often, you can build faster circuits if you're willing to use more gates (of course, that has its limitations too---more hardware can also mean slower hardware, because it uses up a lot of space, however, the savings in computations usually wins out).