Given N data inputs, there are ceil( lg ( N ) ) control bits.

You'd think there would be nothing new to learn from implementing an 8-1 MUX from smaller MUXes that you didn't already learn from implementing a 4-1 MUX and a 5-1 MUX.

Once you see the differences between a 4-1 MUX and an 8-1 MUX, it becomes easier to handle, say, 16-1 MUXes. Usually, you need two or three related examples to see a pattern. Often, it's too difficult to see a pattern using only a single example or even two.

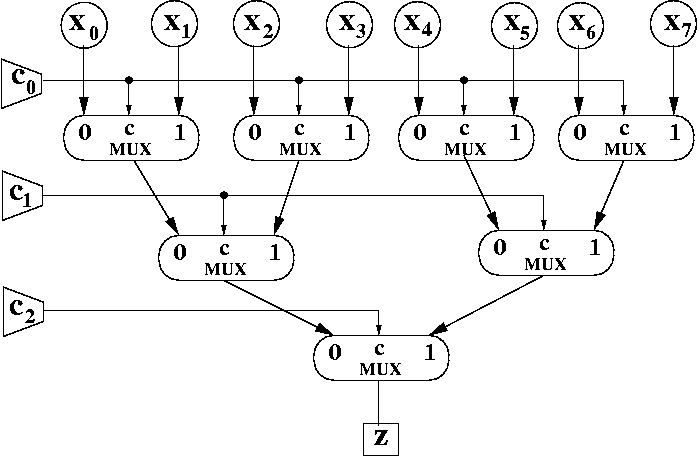

We won't specify the behavior of an 8-1 MUX using a table, since we are going to implement a standard 8-1 MUX. A standard 8-1 MUX treats the c2c1c0 as a 3-bit UB number. Thus, c2c1c0 = 111 selects x7 because valueUB["111"] = 710.

Think about an 3-bit UB number, c2c1c0. What happens when you change c0 from 0 to 1 or back? How does the base value change? It changes from being an even number to being an odd number and back, depending on the value of c0.

How about changing the value of c1 from 0 to 1 or back? this modifies the value by plus or minus 2. For example, if you had the 3-bit number 101, then flipping c1 changes the value from 7ten to 5ten. That is, changing c1 from 0 to 1, increases the value of the number by 2 (in UB), and changing c1 from 1 to 0, decreases the value of the number by 2 (in UB).

Similarly, changing c2 from 0 to 1, increases the value of the number by 4 (in UB), and changing c2 from 1 to 0, decreases the value of the number by 4 (in UB).

Let's see how that helps us to understand what's going on. Suppose the control bits have the following value: c2c1c0 = 101. This means we want to select x5.

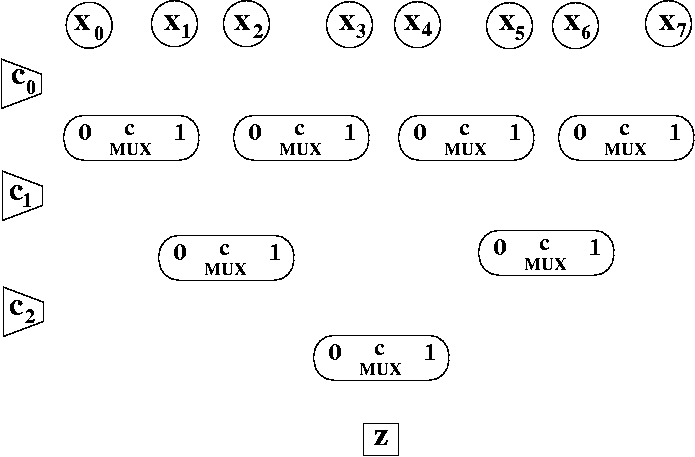

Let's see what happens at each step.

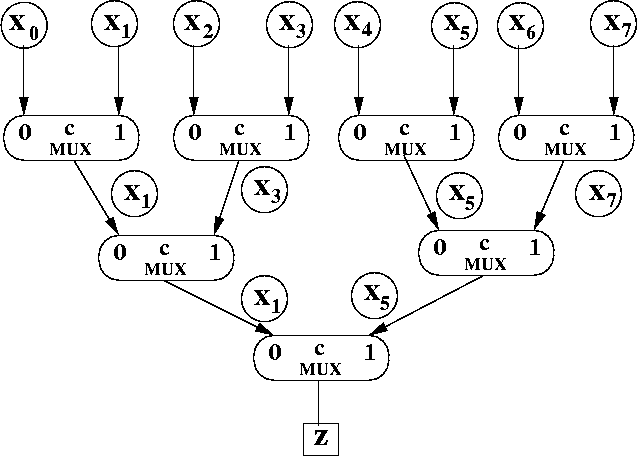

As you can see in the diagram, this selects the inputs with odd valued subscripts.

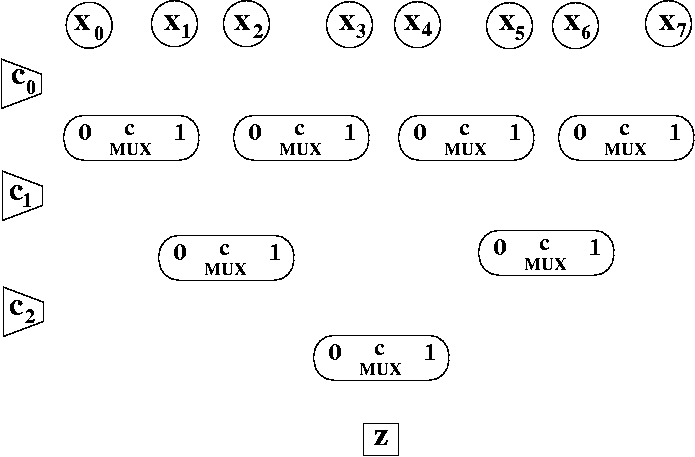

The control bits were removed to make the diagram easier to read. However, in reality, they would still be there.

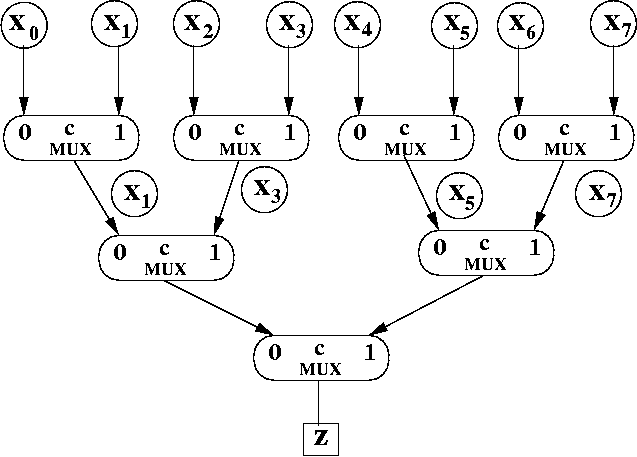

Now imagine that we divide each of those indexes by 2. Instead of x1, x3, x5, and x7, we'd imagine them to be x0, x1, x2, and x3.

In that case, we'd be using control bit c1 to decide between even and odd again. Even though we won't rewrite the index values in the diagram below, effectively, that's what's happening.

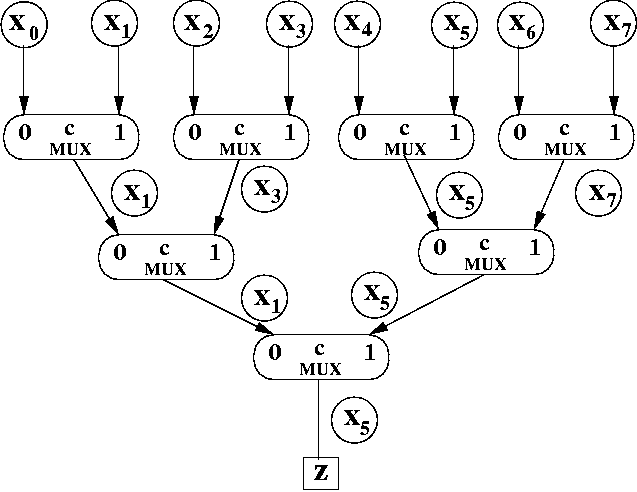

x1 and x5 made it past the second row of MUXes. They were the "even" indexes once you divided the index number by 2 (0 and 2).

Since c2 = 1 in our example, this picks x5

The result of the integer division is either even or odd. If ci = 1, it picks the "odd" index (i.e., input 1 of the MUX). If ci = 0, it picks the "even" result (i.e., input 1 of the MUX).

Generalization is the opposite of deduction. In deduction, you are given a formal set of deduction rules, and some facts, and you use those rules to deduce new facts. Thus, from a small number of axioms (facts), you can show many different facts (theorems).

Even though mathematics appears to be about deduction, many of the theorems came from staring at examples, and trying to create some theorem from it, and then trying to prove it works.

Right now, you've seen how 4-1, 5-1, 8-1 MUXes work. You might still discover that there are ways to tweak the MUX problem that forces you to revise your observations. Thus, certain observations that seem to work in a few examples, may not hold up as you look at different examples.