Given N data inputs, there are ceil( lg ( N ) ) control bits.

When N = 5, ceil( lg ( N ) ) = 3. Thus, there are 3 control bits. With 3 control bits, you can specify one of 8 different bitstring patterns. However, you only need 5 for a 5-1 MUX. What do you do with the other 3?

There are two choices:

Even though the don't care approach seems unsatisfying, we see this happen a lot. Think about string functions in C. For example, strcpy() takes two char * arguments. Neither argument must be NULL. However, strcpy() doesn't check for the error (and how would it inform the user, even if it did check?). Thus, your program core dumps if either argument is NULL.

Thus, strcpy() takes a "don't care" approach to invalid input. That approach leads to core dumps when the input is invalid. It's the "user beware" approach.

We'll take this approach as well, mainly to illustrate that this "don't care" approach is commonly used. It may be, when you're at a job, you won't be able to take such an approach, but at least, you'll know it exists.

Here's the standard way to specify a 5-1 MUX. Recall that we treat c2c1c0 as a 3-bit UB number, and this 3-bit control input selects an input numbered 0 though 4.

In fact, the row number also refers to the input being selected. The row number is the base 10 value of c2c1c0.

| Row | c2 | c1 | c0 | Operation |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | z = x0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | z = x1 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | z = x2 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | z = x3 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | z = x4 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | z = don't care |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | z = don't care |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | z = don't care |

So if you're asked to specify the behavior of a MUX in a truth table, you should draw a table similar to the one shown above.

Here's how to specify a 5-1 MUX where the don't cares are different values.

| Row | c2 | c1 | c0 | Operation |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | z = don't care |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | z = x1 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | z = x2 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | z = x3 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | z = x4 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | z = x5 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | z = don't care |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | z = don't care |

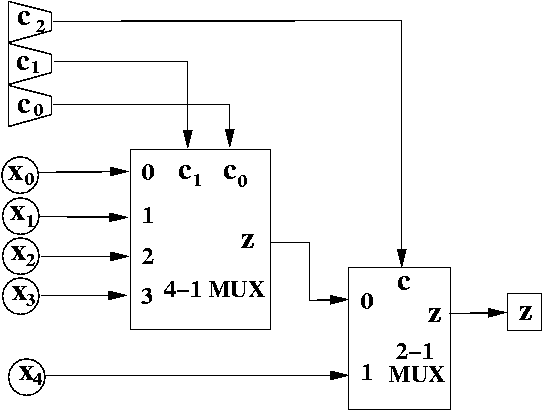

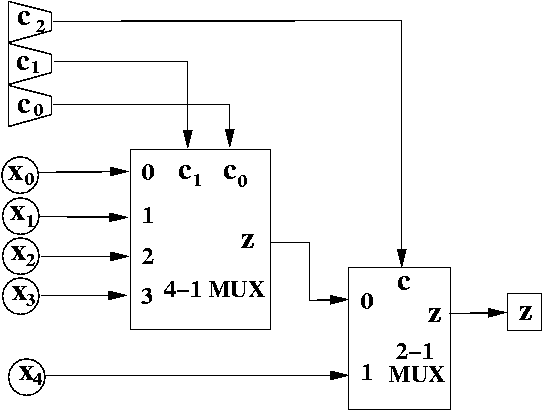

Another approach is to build the 5-1 MUX using other, smaller MUXes.

For example, we can implement a 5-1 MUX using using a 4-1 MUX and a 2-1 MUX.

If c2 is 0, then we know the MSb of the value is 0, thus the choices are 000, 010, 010, and 011, which is exactly what we hooked up to the top.

If c2 is 1, then we know we must have selected 100two (i.e., x4, since that's the only input index has the MSb equal to 1.

To convince yourself this works, try tracing out what happens when the input is: c2c1c0 = 000 all the way up to c2c1c0 = 100.

Also, see what the circuit does for the don't care values, i.e., c2c1c0 = 101 up to c2c1c0 = 111.

Clearly, the 5-1 MUX still outputs something even when the index is not between 000 and 100, inclusive. (What does it output?)

As an aside, notice I circle x0, x1, x2, x3, and x4 to indicate they're data inputs that are sent from the "outside world".

Notice I triangle c0, c1, and c2 to indicate they're control inputs that are sent from the "outside world".

Finally, I square z to indicate it's an output going to the outside world.

The above 5-1 MUX implements the following truth table.

| Row | c2 | c1 | c0 | Operation |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | z = x0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | z = x1 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | z = x2 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | z = x3 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | z = x4 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | z = don't care |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | z = don't care |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | z = don't care |